Forty years since the bitter strike of 1984-85, the threads between cricket and mining are frayed but, just about, still bound.

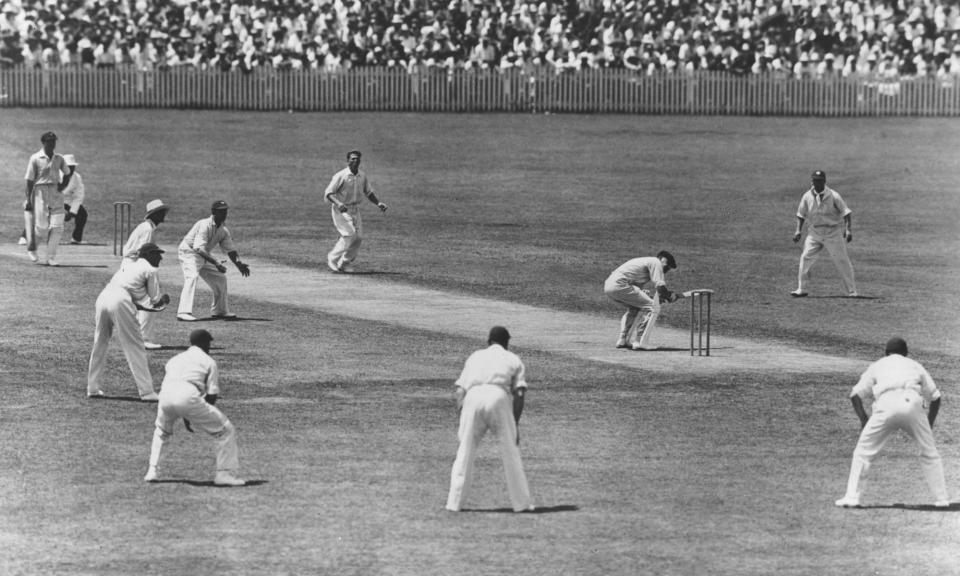

A century or so ago the backbone of English cricket came from the pits. Nottinghamshire won the County Championship in 1907 with seven miners in the team and whistling down the pits for a fast bowler wasn’t just idle fancy. Though presumably you’d have to time your whistle just right, for when the young men had built up immense strength and stamina, but hadn’t yet developed the cursed miner’s cough that came from hours crawling around in the dust.

Related: Cricket Australia cancels men’s T20 against Afghanistan due to concern over women’s rights

Harold Larwood was a pit pony boy at 14 and a night shift worker at 17. Duncan Hamilton’s biography describes Larwood’s underground workplace as “hot as Dante’s hell [where] dim lights offered the only illumination in the intense blackness. He worked in a three foot high tunnel, chipping away at the coal seams and then shovelling up the dirt in preparation for mining.” Larwood dreamt of the light and the sun, and cricket was his escape from the destiny of all of his close male relatives. His partner in crime for county and country, Bill Voce, was a product of the same mines at Annesley.

Huge numbers of clubs grew up around the pits, as they did around co-ops, churches and other industries. David Griffin, the Derbyshire CCC archivist, tells me that lots of colliery cricket on a Saturday started at three and continued until 8.30pm to allow the morning shift to come up and play. In August 1936, Derbyshire fielded a Championship side all born in the county, 10 of them from a mining background.

As part of a Derbyshire Cricket Foundation project, Griffin interviewed two men from Glapwell Colliery Cricket Club about the 1984-85 strike. “Having played throughout that period, I think it impacted not only on cricket but on sport in general and everyday life as well,” one said.

“I don’t recall there being many instances when miners who carried on working throughout the strike ended up on the same field as those who were striking. They were probably such a minority that they probably thought they wouldn’t put themselves through that …

“But I do remember one of the guys from Shirebrook telling me about Shirebrook playing one of the Notts teams, [where the miners] never came out on strike en masse. Halfway through the game, some of the local lads from the village, who weren’t involved in cricket, came up to cause some aggro with some of the Notts team … and they ended up with two of the lads playing for Shirebook … chasing these guys off the ground with a stump.”

There was no escape for professional cricketers from the turmoil, with a number stopped by the police on suspicion of being a flying picket – as, so the story goes, was the unlikely figure of Christopher Martin-Jenkins on his way to a commentary stint. Geoff Miller has spoken about the unfortunate timing of his benefit season. “It was a bit of a challenge holding a benefit in Derbyshire back then. Not a lot of money made by the end of it, and understandably so. Lots of people were out of work because of pit closures.”

Jim Beachill is the chairman and president of Elsecar CC, which sits in a village between Barnsley and Rotherham. “Elsecar was the spark that ignited the strike,” he says. “Elsecar Main had closed in 1983 and many of the men moved to Cortonwood, which was then to be closed with little notice.” Having been promised five years work, the men walked out on 5 March 1984, and the NUM called a national strike a week later.

“I was brought up in the day when everyone worked at the pit or in the workshop, when you could see black-faced miners walking through the town, and hear the noise of the winding wheel taking the miners down,” says Beachill. “When the pit closed, everything changed. The pit maintained the cricket ground along with the council but of course that went too.

“When people are on strike, all the normal things you can do, buy in the shops, you can’t do anymore. You’ve got to beg and borrow, it was a very sombre place, in fact one of the few things people could do was play sport and watch village cricket.

“People from Elsecar were involved in the Battle of Orgreave. The feeling was that the miners were a community together, the strike affected not just the miners but the children, the shops, the families, there was a lot of determination to prevent the pits closing down.”

With the eventual defeat of the strike and the loss of the mines went much of the cultural, sporting and musical infrastructure that had existed alongside. It wasn’t just at Elsecar that the National Coal Board, and the miners themselves, had put money into cricket clubs.

Some clubs didn’t survive the subsequent hollowing out of the villages. Others, like Elsecar, have lived to tell the tale, with one of the buildings on the ground that Beachill describes as “one of the most picturesque in South Yorkshire” put up by contributions from the colliery in the 1950s.

The cricket club runs three senior teams and five junior, and the village too has been resilient. Beachill describes “a thriving community, where a heritage centre stands where the workshops used to be.

“If you ask young people, would you like a job where you won’t see daylight in the winter, digging underground, and you might get killed – they would laugh at you. When our generation goes, people won’t even know what a lump of coal is.” But the former pit villages that continue to play cricket carry the history of industry around not only in their names, but in their heritage.

• This is an extract from the Guardian’s weekly cricket email, The Spin. To subscribe, just visit this page and follow the instructions.

Article courtesy of

Source link