The shortlist for our all-time World Test XI has been picked by Scyld Berry, our chief cricket writer. Now we are asking you, the readers, to pick the players who should make the final team. We have divided our nominees into six categories:

-

Openers (pick two)

-

Middle-order batsmen (pick three)

-

All-rounders (pick one)

-

Wicketkeepers (pick one )

-

Spinners (pick one below)

-

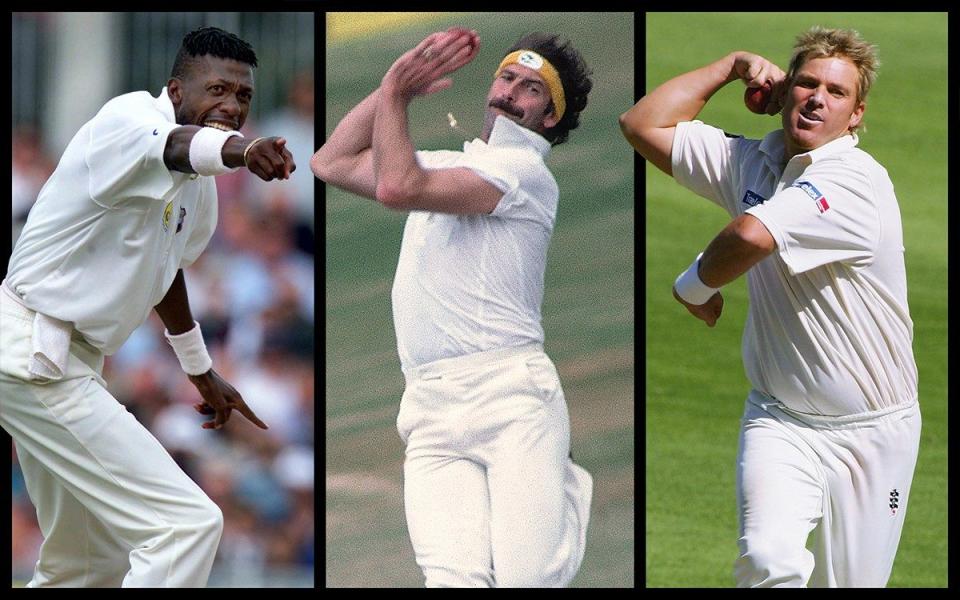

Seamers (pick three below)

Think we’ve missed an obvious candidate? Let us know in the comments. Want to justify your selections? Likewise, let us know.

Voting below is for the spinner and three seamers. Should Sir Garfield Sobers make the final XI (which will be announced tomorrow) the team will already have a second spinner because Sobers could also bowl leftarm orthodox and wrist-spin.

Voting for the openers, middle-order batsmen, all-rounders and wicketkeepers is still open.

Spinners

Syd Barnes (England)

Debut: 1901. 27 matches; 189 wickets @ 16.43

Arguably the quickest spinner there has been, faster than Derek Underwood or Bhagwat Chandrasekhar. Barnes had enormously long, strong fingers which he used to make his legbreak swerve from off to leg before turning: maybe we should call it a leg-cutter but the man himself was emphatic that he was a spinner.

As he aged, he added the offbreak as his main variation and it was said to be barely distinguishable. He still holds the record for most wickets in a Test series, 49 in South Africa in 1913-14, and in only four Tests, all on matting.

Yet he also did hard yards in Australia: 77 wickets in his 13 Tests there at 22 each. He wanted, or demanded, the new ball because there was only one per innings then and he needed the seam to be as proud as he was.

Bill O’Reilly (Australia)

Debut: 1932. 27 matches; 144 wickets @ 22.59

Driven by a dislike of all batsmen (including his own captain Don Bradman), “the Tiger” lumbered in, winding up like a windmill, drew himself up in the crease, and fizzed through leg- breaks and googlies with the emphasis on accuracy, not huge turn.

In the high-scoring 1930s he conceded only 1.9 runs per over, and tied up England’s champion Wally Hammond by bowling at his leg-stump.

He averaged more than five wickets per Test, even in the Ashes: 102 wickets in his 19 Tests against England. Among wrist-spinners, only O’Reilly and Abdul Qadir have been widely advanced as better bowlers than Shane Warne. And when wrist-spin was dying worldwide in the 1980s, O’Reilly kept the flame and message alive in his columns for the Sydney Morning Herald.

Jim Laker (England)

Debut: 1948. 46 matches; 193 wickets @ 21.24

Traditional English off-spin at its best. Holder of the Test bowling record that will live forever: 19 wickets in one game, for only 90 runs, against Australia.

He could make the ball, when dry, fizz through the air – in other terms he must have achieved 2000 revolutions per minute – and he bowled at such a pace that his off-breaks went up above the batsman’s eye-line before coming down and biting.

He was helped by three major factors One, Test pitches were uncovered during play so that Old Trafford in 1956 was sticky. Two, any number of fielders could be positioned behind square on the legside, to form a “leg-trap”, when he operated round the wicket.

Three, there was no limited-overs cricket so nobody had practised running down the pitch to attack him, and few batsmen in those days swept (no helmets to protect them from the top edge). In England he took 135 Test wickets at 18 against 58 at 28 abroad.

At his adopted home of the Oval, the groundsman knew exactly what to prepare, or under-prepare: 40 at 15 in his eight Tests there.

Derek Underwood (England)

Debut: 1966. 86 matches; 297 wickets @ 25.83

It was not until March 2023 that Derek Underwood’s record for most Test wickets in India by a visiting spinner was broken, by Nathan Lyon of Australia.

Underwood took 54 wickets in 16 Tests in India (and there were no neutral umpires in his day) by pushing his left-armers through and getting the ball to grip and kick, hence the nickname of “Deadly.”

In all probability there has never been a more difficult spinner on a worn or wet pitch, because he ran in like a medium-pacer, bowled at approximately 70 mph, and was relentlessly accurate.

Pitches came to be covered in the course of the 1970s which reduced his effectiveness but he kept plugging away. His record of 50 wickets at 31 in Australia is up there with any post-war finger-spinner.

Bishan Bedi (India)

Debut: 1967. 67 matches; 266 wickets @ 28.71

The most classical left-arm spinner was not Wilfred Rhodes, who rather lost his bowling after a triumphant start; or Colin Blythe, whose quicker ball was such that he was rated the fastest bowler in England by CB Fry; or Hedley Verity, who bowled too quickly for purists; but Bishan Bedi.

He glided in, side-on, bracelet on his wrist as every Sikh should wear, and lured batsmen into trying their hand, often applauding a big hit to encourage a fatal one.

It made a beautiful sight. As for his effectiveness, no great spinner has had to follow such a poor pace attack as Bedi: Warne would come on at 50 for two or 70 for three, especially against England, whereas Bedi usually had to contend with two well-set openers batting under minimised pressure, until finally Kapil Dev emerged.

Still, Bedi was the role model, and almost as effective away from home, his flight and guile often taking pitches out of the equation.

Abdul Qadir (Pakistan)

Debut: 1977. 67 matches; 236 wickets @ 32.80

He had an old-fashioned fast bowler’s temperament. Sometimes he was not in the mood. At others he was as hostile and fiery as any fast bowler, even more theatrical and threatening than Shane Warne, while his googly was always more potent than Warne’s.

The lacuna in his record is that he was much more effective in Pakistan than anywhere else: 168 Test wickets at 26 at home, 68 at 47 away.

But maybe he would have benefited, more than any other of his fellow candidates, from DRS. Impact inline, yes, hitting the stumps, yes!

Had he been bowling today his googly would surely have trapped many more batsmen than the nine LBWs he secured in 27 Tests abroad, where again the umpires were not neutral.

Anil Kumble (India)

Debut: 1990. 132 matches; 619 wickets @ 29.65

Imagine being in the dentist’s chair for hours on end: that was what it was like to face Anil Kumble. With quick top-spinners drifting into the right-handed batsman, he drilled away and occasionally turned one from leg.

On a wearing pitch he was as penetrative as they come: never play back, because he was so quick through the air and the over-spin tended to make the ball keep low.

At Delhi in February 1999 he became the second, after Jim Laker, to take all ten wickets in a Test innings, although “only” 14 in the match against Pakistan.

Like almost every spinner he was more effective in the conditions where he was brought up (Kumble started on matting pitches in south India): 350 wickets at 24 at home, 269 at 35 away. But wherever he was, Kumble drilled and drilled until 619 Test batsmen submitted.

Muttiah Muralitharan (Sri Lanka)

Debut: 1992. 133 matches; 800 wickets @ 22.72

The closest that any Test attack has come to being a one-man band was Sri Lanka’s when Chaminda Vaas was not playing and both the stock and shock bowling fell on Muttiah Muralitharan.

His “doosra” was not a thing of beauty, but otherwise he bowled his off-breaks as straightforwardly as his right elbow allowed, with his wrist imparting a unique flick that made the ball spin like a top.

In the comparison with his closest rival, it is key that Shane Warne was always trying to take wickets – apart from the occasional stalemate when he went round the wicket and aimed at the righthander’s legs – whereas Muralitharan was defensive, admitting that his first objective in an over was to stop going for a boundary.

Like almost every spinner though, there was the disparity between home and away: 493 wickets at 19 at home, 269 at 35 away (in no other country did he take 50 wickets).

Shane Warne (Australia)

Debut: 1992. 145 matches; 708 wickets @ 25.41

Never has cricket seen such a magician as Shane Warne. After his right shoulder injury, 200 wickets into his career, he still took 500 more wickets; he bowled only two types of delivery, the legbreak and slider, yet he gave the convincing impression that there were infinite tricks in the bag of the maestro.

And here is the spinner who was devastating at home and even more so away: 319 wickets at 26 in Australia, 389 at 25 away (and no mopping up minnows because he played only three Tests against Bangladesh and Zimbabwe combined).

Like Viv Richards, and very few others, he never looked as though he was beaten – except, possibly, when his shoulder would not let him bowl a googly any more and Sachin Tendulkar went after him in India, where Warne’s average was 45 (the only country where it was over 30). His reputation has not diminished since his passing. Nor should it.

Ravichandran Ashwin (India)

Debut: 2011. 92 matches; 474 wickets @ 23.93

Is there any need to look further if this ultimate match is going to be staged in India? Or anywhere in Asia, for that matter, as he has taken well over five wickets per Test and 387 in that continent at only 21 each.

And if the opposition are coming from another galaxy, maybe there are unfamiliar with Ashwin’s variations, of which no finger-spinner has surely had more.

Ashwin begins to spin his web at the start of his run-up, arms wheeling away, making a new batsman wonder which arm he is going to bowl with, never mind whether it is an off-break or not.

The spiderman can then deliver every conceivable type of ball, at good pace, so there is little hope in playing back. Playing carrom (the Indian board game in which pieces like draughts are moved by flicking a finger) has enabled him to master what very few non-Asian spinners (perhaps Australia’s Jack Iverson and John Gleeson) have had in their armoury.

If the wicketkeeper in this side cannot bat so high as number seven, Ashwin could.

Vote for a spinner – please select one candidate

Seamers

Dennis Lillee (Australia)

Debut: 1971. 70 matches; 355 wickets @ 23.92

The best fast bowler of the amateur era i.e. before World Series Cricket in the late 1970s. Harold Larwood bowled quicker than anyone before Bodyline probably, often bouncers; Frank Tyson bowled quicker still, on a full length; and Fred Trueman was a tearaway before settling down to fast-medium outswing.

Dennis Lillee combined in himself these attributes: bouncers, yorkers, outswing, leg-cutters and ferocity. And his greater height generated steeper bounce.

He also brought his own passion to bear, and could bowl for almost a session to sway a match Australia’s way: it was a strong captain who could take the ball out of his hand. To his 355 Test wickets, his 67 for WSC Australia could be added.

Like a prophet, he was not venerated sufficiently in his own land, but the MRF Foundation he set up in Chennai has produced India’s fast bowlers.

Sir Richard Hadlee (New Zealand)

Debut: 1973. 86 matches; 431 wickets @ 22.29

The complete fast-medium bowler, after he had started his career and run-up “like Groucho Marx chasing a waitress”, as John Arlott phrased it immortally. He used his stints at Nottinghamshire to refine his method, and the shrewd accountancy mind which he had inherited from his father Walter (a New Zealand captain) to maximise his career.

Given a pitch with a hint of green, nobody was more likely to finish with a five-fer because, long before data, Hadlee programmed his mind to make the most of his opponent’s weaknesses. New Zealand’s cricketers had long been subservient to Australia’s.

Hadlee took 15 wickets at Brisbane in 1985-6, won NZ’s first Test series in Australia, and finished with staggering statistics against them: 130 wickets at only 20 runs each in his 23 Tests against Australia.

Such was his self-motivation and fitness, he surpassed Ian Botham’s world record of 383 Test wickets and raised the bar to 431, taking 34% of NZ’s wickets in the process. Of the ten bowlers here listed, only Shaun Pollock was Hadlee’s equal as a batsman.

Malcolm Marshall (West Indies)

Debut: 1978. 81 matches; 376 wickets @ 20.94

If Richard Hadlee was the first who could be acclaimed as the complete fast-medium bowler, Malcolm Marshall was the first who could be acclaimed as the complete fast bowler.

He generated pace from his twinkle-toed run-up and fast-twitched shoulder muscles, strengthened from an early age by playing beach cricket in Barbados.

He also had an unquenchable thirst for wickets, whether for Hampshire or West Indies, and the competitive edge to master every type of delivery: inswinger, outswinger, leg-cutter, off-cutter, bouncer, yorker, rib-breaker.

He even rolled over England at Headingley with a broken arm. Had he been awarded a central contract, he would have taken more wickets for West Indies, or maybe he did not need to rest, such was his athleticism.

He was in his sixth year of Test cricket before West Indies lost a match. Another amazing thing: Marshall said in his autobiography that there were a lot more talented cricketers among his contemporaries when growing up in Barbados but they never entered the hard-ball club system.

Wasim Akram (Pakistan)

Debut: 1985. 104 matches; 414 wickets @ 23.62

Australia’s Alan Davidson had been the finest left-arm pace bowler, basing his game on new-ball swing. Wasim Akram turned up at Pakistan’s net-practice, never having been coached, and did it differently.

His “split action”, for a start, front foot pointing down the pitch, back foot in almost the opposite direction, put tremendous stress on his body yet it was so natural for him that he kept going until he was recognised as the best left-arm pace bowler ever.

His other natural asset was the whippiest of bowling arms. Growing up under Imran Khan’s captaincy, he could of course reverse-swing an old ball – even more than he conventionally swung the new ball – and he introduced the new angle of bowling it from round the wicket. Actually Wasim Akram was re-introducing this left-arm angle.

George Hirst of Yorkshire had swung the new ball from round the wicket before the First World War, but the effect was much the same: “like a fast throw-in from cover” was the graphic description which applied in both cases. A rousing hitter when he wanted to be.

Waqar Younis (Pakistan)

Debut: 1989. 87 matches; 373 wickets @ 23.56

It was one of the great mishaps that Waqar suffered a stress fracture in his back in 1992. Before then he was arguably the most thrilling sight ever seen on a cricket field, because nobody sprinted further and faster to the bowling crease.

In his last nine Tests before that back injury, all in Pakistan, on the world’s most unresponsive pitches, he had taken 61 wickets at 14 each.

The ball made a thrilling spectacle too, because Waqar’s captain Imran Khan had taught him reverse-swing: from Waqar’s low arm, when he was reversing, the ball would start angling towards the slips.

From two feet outside off stump, it would change course and demolish the batsman’s leg stump or toes. Thus armed, though slower, Waqar continued his Test career for another ten years without ever being quite so electrifying as he was at his peak.

(In 1991 Waqar took 113 championship wickets at 14 each for Surrey and Wisden noted: “It is doubtful whether anyone has bowled faster or straighter in an English season… with an astonishing two-thirds of his victims bowled or lbw.”) The world then became fussy about methods used to obtain reverse-swing.

Shaun Pollock (South Africa)

Debut: 1995. 108 matches; 421 wickets @ 23.11

Allan Donald, Makhaya Ntini, Dale Steyn, Morne Morkel, not to mention Jacques Kallis: some tremendous pace bowlers took South Africa to the top of the Test ladder within 20 years of their readmission.

But the most skilful and the meanest of all was Shaun Pollock, in two ways. None of them was more likely to hit a batsman than Pollock when he started and careered to the crease like a bucking bronco.

World cricket in the mid-1990s rang with the sound of helmets which Pollock hit (his father Peter had specialised in hitting heads wearing caps).

When he shortened his run and calmed down a bit, he became the meanest of fast bowlers in terms of his accuracy, giving the batsman nothing, maximising the new ball, zipping both ways.

He had all the ingredients of a top-class batsman too, averaging 32, and could have batted regularly at number six, although he had not the time and energy for more than two Test hundreds.

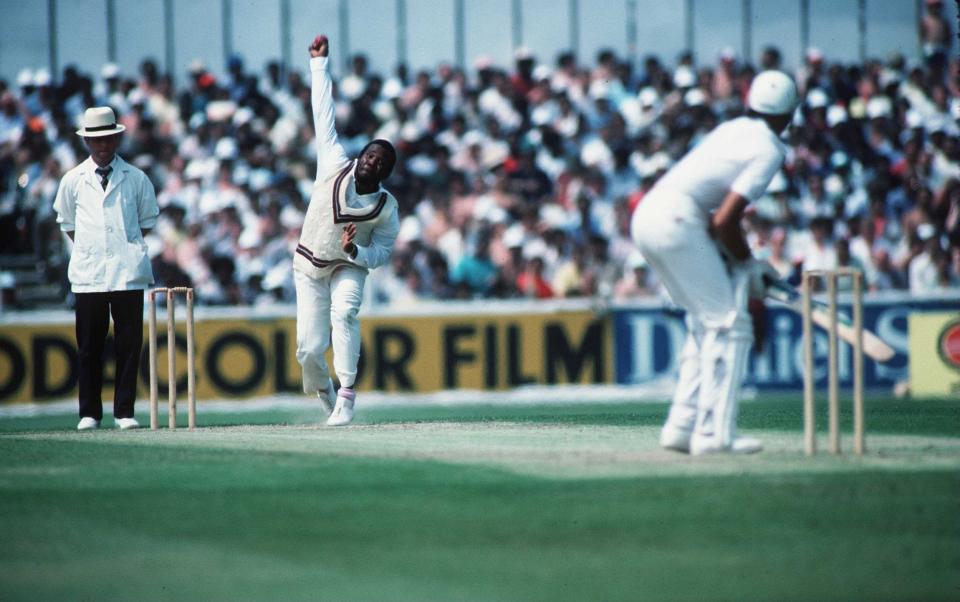

Sir Curtly Ambrose (West Indies)

Debut: 1988. 98 matches; 405wickets @ 20.99

Every bowler gets taken apart one day, in some format or other, even the greats (like Dale Steyn at the hands of AB de Villiers in the IPL). But not Curtly Ambrose. Nobody took apart King Curt.

When Brian Lara threatened to do so one day for Warwickshire against Northamptonshire, a beamer whistled past his nose. Ambrose had the height and pace, whether with new ball or old, to bowl an unhittable length.

He kept doing that throughout his career, maybe sacrificing some wickets by not bowling a fuller length but always in control.

The only bowlers to have taken 200 Test wickets at an average below 21 are the West Indians Ambrose, Malcolm Marshall and Joel Garner. Arguably, and certainly statistically, the supreme spell of fast bowling was Ambrose’s seven wickets for one run in Perth in early 1993: Australia, 86 for two, were flattened for 119.

When Ambrose was angry or super-motivated and steaming in, for those who never saw him, his trajectory was like Jofra Archer’s when bowling at Steve Smith at Lord’s in 2019. Unplayable.

Glenn McGrath (Australia)

Debut: 1993. 124 matches; 563 wickets @ 21.64

“They say the folk from Narromine/Are narrow-minded folk.” So the bush poet sang, and he was nearly right, but not quite. Glenn McGrath, from this outback NSW town, was single-minded not narrow-minded.

He was the lone wolf, bowling in his backyard outside Narromine, determined to use his natural advantages to become a pace bowler for Australia; and, as school cricket was no platform, he moved to Sydney, lived by himself in a caravan, and rose through the ranks of grade cricket.

Height, metronomic accuracy, the predator’s instinct and the new ball led to the most Test wickets by any pace bowler until James Anderson usurped the title.

No more than fast-medium in pace, he was blessed with arguably the best slip cordon of all time – Mark Taylor/Mark Waugh/Shane Warne/Ricky Ponting – and he kept them in business for 15 years by making batsmen fish at the bouncing ball on fourth stump.

James Anderson (England)

Debut: 2003. 179 matches; 685 wickets @ 25.99

He would be the least in speed of these ten pace bowlers but also, in compensation, the most accurate. A master-craftsman who could nominate where the ball was going to pitch and which part of which stump it would hit.

And, as another compensation for being the slowest of these ten, he has been the longest-lasting, getting better and better for 20 years since his debut.

One illustration of how he has kept improving is that he has adapted his bowling to one Test country after another, including – or especially – the UAE, until he has mastered conditions in them all; a second is how his Test average has gone down in the course of time; and a third is how he has been the most successful Test bowler ever after reaching 40 (28 wickets, and counting, at 17 each).

Only Sachin Tendulkar, a batsman, has played more Tests; only two spinners have taken more wickets. Central contracts or not, Anderson has become unique.

Mitchell Johnson (Australia)

Debut: 2007. 73 matches; 313 wickets @ 28.40

Of all the bowlers there have ever been, who would you be most afraid of facing? Personally, Mitchell Johnson. Surely nobody has come closer to making a cricket ball defy physics and accelerate off the pitch than Johnson in the 2013/4 series against England.

A long, lupine, lope then the bracing of every muscle into the form of a human catapult: awesome to watch, awful to face. He also had a wider range of angle to attack you, from over or round the wicket, than any right-armer.

After being ridiculed by England supporters earlier in his career, Johnson had the motivation, pace and innate hostility to rip England to shreds in 2013-4, with 37 wickets at only 13.97 each.

He took a wicket every 30 balls, in other words in every spell. Or put it this way: in that series Peter Siddle was the equal of any England seamer, Ryan Harris was a street ahead of Siddle, and Johnson was a street ahead of Harris.

In the next Ashes series in Australia, when he was a Telegraph columnist, retired, he was walking into the nets at Perth for a photo-shoot when he turned his left arm over. A stump fled its socket and would have landed in the Indian Ocean without the netting.

Vote for the seamers – please select three candidates

Voting for the opening batsmen, middle order, all-rounders and wicketkeepers is still open. The readers’ team, alongside Scyld Berry’s preferred XI, will be announced on Friday. Voting in all polls closes on Thursday at 8pm.

Article courtesy of

Source link