While Baz-ball, or more strictly Ben-ball, will become all the rage at every level of cricket in the UK if England win the Ashes this summer, one aspect is guaranteed not to become popular: the act of enforcing the follow-on.

The practice of making a team follow on – when at least 200 runs behind on first innings in a Test, or 150 in other first-class games – has been going out of fashion, and the sight of James Anderson and Stuart Broad limping off the Basin Reserve is not going to bring it back.

It is a strange convention in cricket, or rather Law 14. Stranger still, it used to be compulsory for the team lagging behind on first innings to follow on until 1900, when the University Match degenerated into uproar after Cambridge deliberately bowled wides in order that Oxford would have to bat in the fourth innings – not the third – on a deteriorating pitch.

“On returning to the pavilion (after deliberately bowling wides) the Cambridge Eleven were hooted at by the members of MCC, and in the pavilion itself there were angry scenes, many members losing all control over themselves,” Sir Pelham Warner, himself a Blue, recorded in “Lord’s”. The law was changed later that same year to make the follow-on optional; it was realised that making it compulsory penalised the team that had played better cricket in the first half of a match.

Over the course of time enforcing the follow-on has been a very successful tactic in Test cricket, even though it has become ever less common. It has served to keep a foot on the opponent’s throat. On 293 occasions it has been applied since 1877, and the team that has enforced the follow-on has won on 230 occasions.

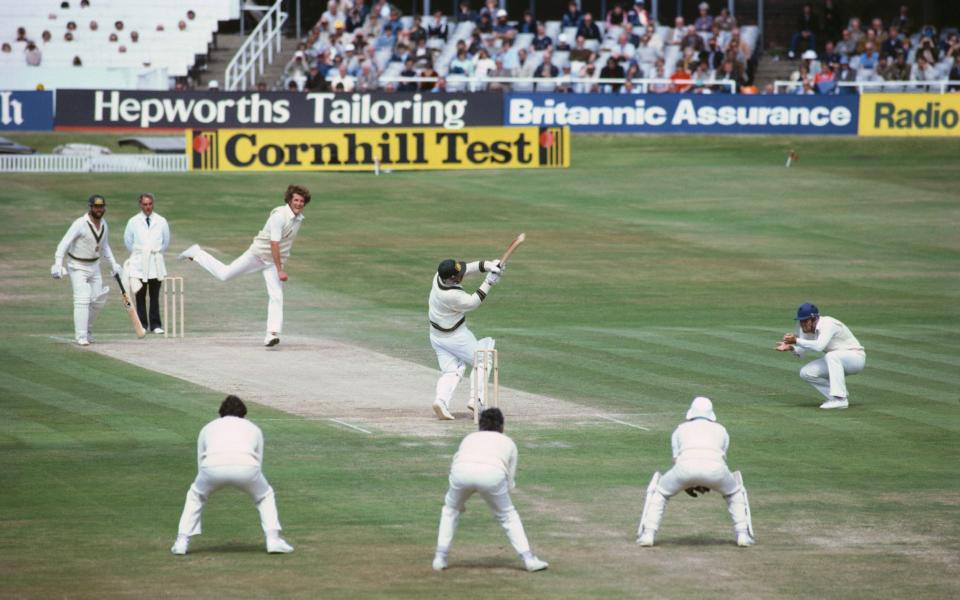

On only three occasions before the Wellington Test has enforcing the follow-on ever resulted in defeat. The first was when it rained heavily one night in Sydney in 1894-5 and Australia suddenly found that a nominal target to beat England was no such thing; the second was in another Ashes Test, at Headingley in 1981, when Lord Botham and the late Bob Willis turned the tables.

In spite of these two freak occurrences, the follow-on remained a standard and sensible policy into the 1980s, because of the rest day. Before the era of global professionalisation – when only England, in effect, had professional cricketers – you never had to play cricket for more than three days in a row. Tests in England began on Thursday; on Sunday you played golf or put your feet up, reducing the chance of stress fractures and other injuries, until the rest day was abolished in the 1980s.

The third occasion had a widespread impact on Test cricket’s psyche. It was the Kolkata Test of 2001, arguably the greatest match in the greatest series of fewer than five Tests. Steve Waugh’s Australia made India follow on but VVS Laxman, dashingly, and Rahul Dravid, doggedly, turned the tables in a stand of 376. India won by 171 runs.

Waugh did not cease to enforce the follow-on – why would he when he had Glenn McGrath and Shane Warne? – and he never again became a cropper. But, since that seminal moment, lesser teams have increasingly favoured the option of batting again and giving their bowlers a break rather than a breakdown. The trend now is to enforce the follow-on only if the opposition has been dismissed in fewer than 60 overs, leaving bowlers relatively fresh.

Had Ben Stokes known in advance that New Zealand would launch their second innings with an opening stand of 149, he might have batted again, but that is the wisdom of hindsight. A major consideration is that the Basin Reserve tends to become flatter and deader as a Test goes on, so batting last should hold no horrors, whereas pitches in other countries wear and tear.

A second consideration is that New Zealand have traditionally been the best team in the world at dogged resistance, and if Stokes had batted instead of enforcing the follow-on, New Zealand could still have batted for many long hours in the fourth innings. It was at Wellington in 1983-4 that Bob Willis’s England took a similar lead on first innings to Stokes’s team, 244, then had to suffer while New Zealand piled up 537 to draw. Nick Cook played the Jack Leach role with 66.3-26-153-3.

If enforcing the follow-on does not become fashionable, then encouraging specialist batsmen to bowl more should. When the pitch has gone flat and pace bowlers are exhausted, this is the time for novelty. Mike Gatting nipped in with the wicket of Martin Crowe in 1984, just as Harry Brook did with that of Kane Williamson, who had never seen Brook bowl before.

England have Joe Root as an able second spinner but they need an occasional medium-pacer as well if, and when, Stokes’s left knee prevents him bowling.

Article courtesy of

Source link