Saturday saw not only one of the hottest days of this cricket season but one of the more poignant. It was the last game on the ground where Siegfried Sassoon, finest of war-poets and bravest of men, used to play.

In early July the cricket club was given three months’ notice to quit. If £280,000 is not found in a hurry, it will go the same way as the neighbouring football ground where grass is already climbing the goalposts.

After winning the Military Cross for capturing a German trench single-handed and carrying one of his men back to safety, Sassoon was lionised by London society, then vilified for being the ultimate whistle-blower. Having been there, and done that, he dared to issue a proclamation that the First World War was not worth millions of lives. The establishment threatened to have him shot for, of all things, cowardice; he voluntarily returned to the trenches as he sympathised so much with his men.

Sassoon moved to Heytesbury in 1933. In addition to playing cricket in the grounds of the estate, he walked through the woods on the surrounding hills with his secateurs and never-fading memories. “He was still having terrible nightmares in 1953 when I first met him,” said Dennis Silk, a Cambridge and Somerset batsman befriended by Sassoon before becoming Warden of Radley. According to Sassoon, “the worst thing was looking at your watch before going over the top, as the seconds ticked, and you realised most of the men would be dead in ten minutes.”

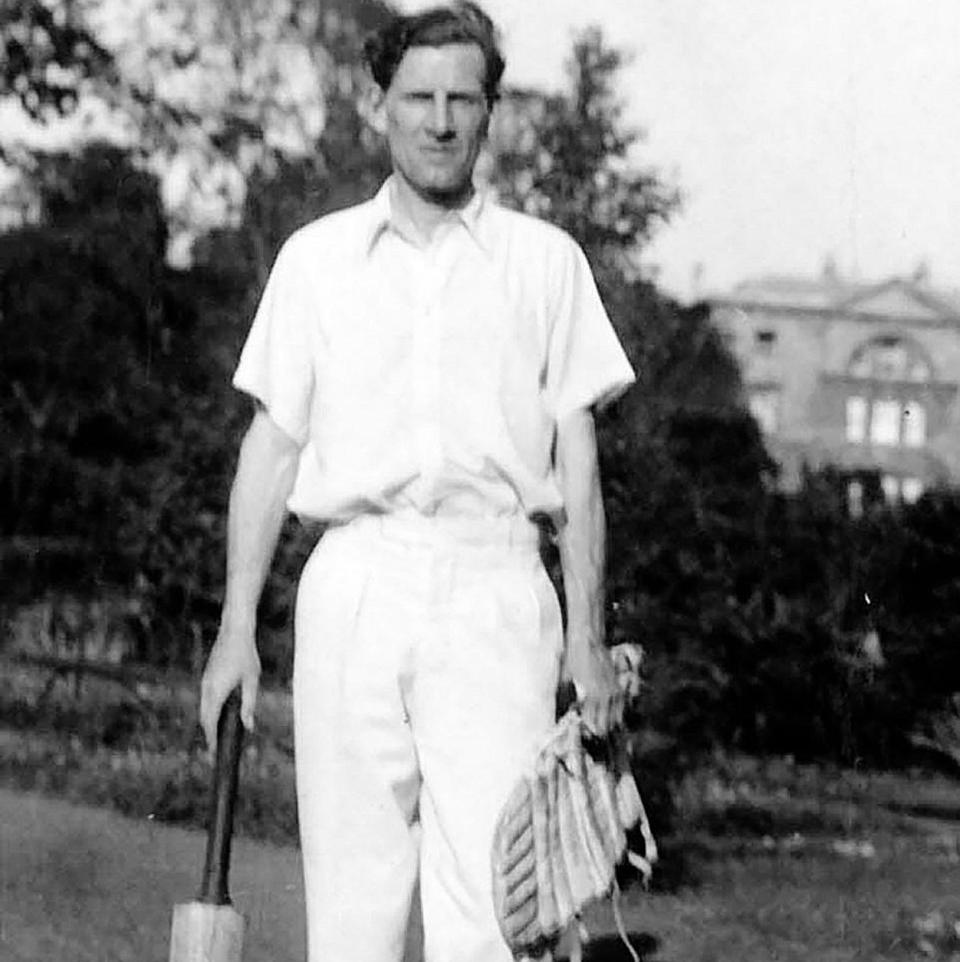

An essay worthy of Sassoon was written by David Foot, the late West Country writer, which is reproduced in a new anthology, “Footprints”. During his research Foot found that Sassoon would have two estate workers open the bowling, Jim Kitley and Henry Reynolds, while he himself would bat in the lower order where he was “very ordinary”. The days had gone when he could hit the winning run, as Sassoon described in Memoirs of a Fox-hunting Man, to win The Flower Show match.

“He positioned himself as of right at mid-on, a gaunt, statuesque figure,” Foot wrote of Sassoon’s fielding. “When the batsman struck the ball firmly in his direction Siegfried remained stiffly to attention, allowing it to crack against his unprotected shins. The rest of the team would wince and do their best to suppress gentle guffaws. He would then, in very much his own time, stoop to pick up the ball and return it underarm to the bowler.”

No shinpads either. It does not seem right that an officer who fought in the trenches, who still had scars on the back of his neck where two bullets from a German sniper had not missed, should have a cricket ball adding to his pains; but such was his sense of duty.

Foot records another example of the importance of cricket to Sassoon. His party trick was recalling the initials of first-class cricketers, especially “those of Kent players before the First World War” and, above all, those of his hero Frank Woolley, or “Woolley – F.E”.

Trees in the woods, notably beeches, were barely tinged when Heytesbury began their last game against a side raised by their club chairman Justin Wagstaff. A Brimstone butterfly was inspecting the square before seeking shade. The ground slopes down to the village and the River Wylye, which is still limpid enough after descending from Salisbury Plain for kids to swim.

Halfway through the chairman’s innings Tommy Reynolds came on to bowl, up the slope, just like his great grandfather. A sturdily built figure, he ran in, hopped, wheeled his arm over and had a wicket caught at square leg from a full toss.

A few overs later Graham Kitley, Heytesbury’s captain, brought himself on, bowling down the slope just like his grandfather did, but not for long. Jim was trapped in Singapore and when he returned after three-and-a-half years from a Japanese prison camp his legs were so covered in boils and sores he could not play cricket again. So said John Kitley, son of Jim and father of Graham, who was watching the final game.

As a nipper John Kitley used to sit on the roller – the same one as now – and watch Sassoon walk down from Heytesbury House to have a net against his father. Sassoon would habitually wear trousers too short and a funny hat “like the Pope’s” and was too taciturn to speak. Sassoon and his opening bowler were soon in the same boat: Jim Kitley, after returning from the Second World War, “woke up sweating every night of his life until he died at 88”.

Tea made a welcome break from the heat. The tea lady had started making sandwiches at 10.30am, but did not cut them up until 1.30pm, so they would not curl. In Sassoon’s day the players went to the Angel Inn for tea, and drinking afterwards. An omen when it closed earlier this year.

I have always had a soft spot for Heytesbury because I played my first league game there after sepsis, and it was about the only time I scored more runs than I conceded. Again, for some reason, they did not slog me down the slope and into the field behind the arm; they must have mistaken me for a wily rather than Wylye spinner.

“Last 12 overs!” Captain Wagstaff announced after our second drinks break. Not last 12 overs of the season, but ever, on this blameless ground. Soon our wicketkeeper shouted “Last over!” Wagstaff himself bowled it, and though Heytesbury fell almost 20 runs short, their opening batsman reached his century.

Sassoon might have been disappointed with the result, as well as with those descendants of his – they are not unanimous – who are selling the ground. Indeed, the proposals have split the poet’s surviving descendants, with his granddaughter, Kendall Sassoon, and her children opposed to the scheme.

She told The Telegraph: “I’ve told the trustees ‘no’ don’t sell the land, but donate it to the village for community use. The cricket club was very important to my grandfather. He adored it. He found peace there after all he’d been through.” Others among the trust’s beneficiaries, including members of the wider family, are in favour of a proposed sale.

If the sale goes through, nothing of him will remain except his writing and a Spartan gravestone in the churchyard at Mells which reads: “Siegfried Loraine Sassoon 1886-1967 RIP.” Or, as he might himself have said: “Sassoon – SL.”

After the handshakes the Heytesbury players gathered to sit on the square, as a wake. The sun drowned behind the beeches. And that was the end of The Farewell Match.

To pre-order a copy of “Footprints” by David Foot click here

Article courtesy of

Source link